“He’s not anti-American; he’s just against the bad parts of America.”

“He’s not anti-American; he’s just against the bad parts of America.”

“They’re not attacking white people, just attacking the systems of racial exclusion.”

“Patriotism means criticizing the bad just as much as it means celebrating the good.”

“Of course all lives matter; but our system doesn’t reflect that premise, so saying ‘black lives matter’ is an effort to make the promise a reality.”

“It’s not an attack on cops; it’s an attack on bad, racist cops.”

These are common phrases, which come with all the best intentions. And they often do reflect reality.

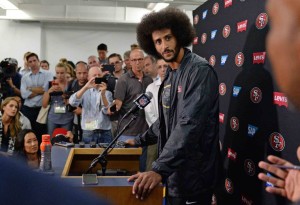

But there’s a real danger here as well. Are you sure Colin Kaepernick isn’t anti-American? Are you sure that the black lives matter protester truly believes the American dream can be redeemed? Are you sure she sees herself as a patriot? Are you sure they value blue lives in general and are merely trying to criticize the bad practices of a few?

Or are you displacing onto them what you want their protest to mean?

This is an important question, and one that reveals the diverse ways in which the American cultural landscape is deracinated. The most obvious form of racial depoliticization is to attack protest as illegitimate. We see this when Colin Kaepernick is denied the right to speak—because he’s not ‘really’ black, because he’s rich, because he’s pampered, because he’s not protesting ‘in the right way’ and so forth. Here, the right of the speaker to bring the experience of black life into contact with white comfort is directly denied.

But this is not the only way in which race is rendered invisible. The same basic process takes place when well-meaning liberals take acts of protest and refigure them, shape them to fit their own narrative structures. To see protest purely as a form of ‘conscientious objection,’ as a call to honor the underlying promise of equality, is also a form of depoliticization. Against radical protest, we dissemble and domesticate. We impose a belief in the larger promise of racial harmony where such belief does not exist.

This act of translation is understandable. Conversation across the boundaries of experience is difficult under the best of circumstances. And the topic of race is hardly the best of circumstances. But this is precisely why we need to be careful.

Not every scream into the chasm of injustice is an invitation to build a bridge.

For those of us who believe in the possibility of rehabilitation, this is a difficult truth to face. It’s deeply uncomfortable to encounter a claim for which we can offer no reparation. Against such cries, we desperately look for points of entry. And this is what leads us to speak the truths (as we see them) that must be buried in their claims.

But in doing so, we replace their politics with ours. And in its own way, that’s equally an act of dismissal, a form of racial violence.

No good answers

So what is to be done? Should we simply stand aside? In some cases, maybe. But there are no pure choices here, no perfect answers. Detaching ourselves entirely from these conversations is clearly no solution. That simply replicates the initial problem: leaving protest to fend for itself within a market of ideas heavily stacked against it.

And after all, my point is certainly not that the goal of racial redemption is purely an invention. That promise is, quite emphatically, not the sole property of White America. And we will do well to honor and reflect the gestures toward this kind of politics which are being engaged. But we can only genuinely honor those efforts if we are capable of recognizing them as choices, rather than as the inevitable and necessary endpoint of racial critique.

So we do have a responsibility to stay engaged. We just have to be careful, willing to live with the discomfort that comes from knowing that nothing we can do is free from harm. We can be allies, friends, amplifications. We can try to lend the legitimacy afforded to us by our social position to those denied such legitimation, while also remaining attentive to the ways that this process always risks overwriting the very concerns we are hoping to assist.

And for any of that to work, it has to come from a place of really listening. Even when that means listening to perspectives we find deeply disquieting.